'A Mince Pye without Meat': Festive Tidings from 1806!

It is that time of year again, it seems. Christmas adverts have been on the television for approximately five months and I think it's finally an acceptable time to allow myself to feel festive. There is a limited window to appreciate mulled wine, cheese plates and putting cinnamon on everything I eat, after all.

As I have been continuing to research Victorian cuisines, recipes and foodways I thought I would turn my attention to the Victorian Christmas, and as it turns out, Christmas is one holiday (unlike Halloween, as my previous post showed) that Victorians did with aplomb. I'm sure everyone reading this is familiar with Dickens's canonical A Christmas Carol in one or another of its iterations; whether you read your well-thumbed copy every year on Christmas Eve, or are a huge fan of the Muppet's film version - it all counts. Published in 1843, A Christmas Carol was one of Dickens's most popular works (six thousand copies were printed on its first run and it soon needed to reprint, its popularity surprising Dickens himself) and it went far to establish the tradition of buying books as Christmas gifts, as well as the Christmas book genre - both of which continue to this day. An excellent overview of how A Christmas Carol began this festive publishing phenomenon, and how print culture in the nineteenth century established a British Christmas identity, can be read in Tara Moore's Victorian Christmas in Print (2009), which I would recommend to anyone interested in Christmas books, traditions, and Victorians. Indeed, at a recent reading

group I hosted we discussed Moore's book and how much the idea of the British Victorian Christmas is still embedded in our culture. Be it romanticised ideas of snowy walks through a foggy London, or John Lewis adverts that evoke ideas of charity and kindness through a Victorian lens, we seem very apt at forgetting that in reality Victorian life was difficult. Not every family had a benevolent employer who had been forced by ghosts to buy them dinner...

What I am interested in, of course, is how food plays in to all of this. After all, A Christmas Carol revolves around the concept of a traditional British Christmas dinner. The novel begins with Scrooge rejecting Fred's invitation to dinner and ends with him buying the Cratchits a glorious turkey, before he rejoins his family for celebrations over a laden table. So, if Dickens's novel began to define our ideas of what Christmas should look like, and a Christmas identity began to be really cultivated in the nineteenth century, it makes sense that the Victorians would have had a lasting influence on British Christmas cuisine.

As the Cratchit's traditional turkey suggests, many of our favourite Christmas foods were also eaten by the Victorians. Mince pies, plum (Christmas) pudding and sprouts all feature regularly in Victorian newspapers and periodicals as part of articles that outline Christmas menus. That isn't to say that all traditions caught on, however. As Moore points out, in Hereford there was a festive tradition that involved 'celebrants impal[ing] a plum cake on a cow horn, then dash[ing] cider in the cow's face' before watching where the cake fell 'as a way of forecasting the next harvest' (Moore 2009: 2). While there are cows-a-plenty in the fields next to my parents' house, I think that's one tradition I will be leaving in 1830.

So I thought I would turn to one Christmas staple that is as popular now as it was in the nineteenth century: the humble mince pie. In origin, the mince pie is not Victorian and even precedes the long nineteenth century. This article explains in more detail that pies with mince in them, or mince pies, can be traced back to far earlier in British cuisine - http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20171208-the-strange-and-twisted-history-of-mince-pies - but I wanted to see what a nineteenth-century take on the mince pie was, thinking that I would bake some authentic festive treats for the aforementioned reading group.

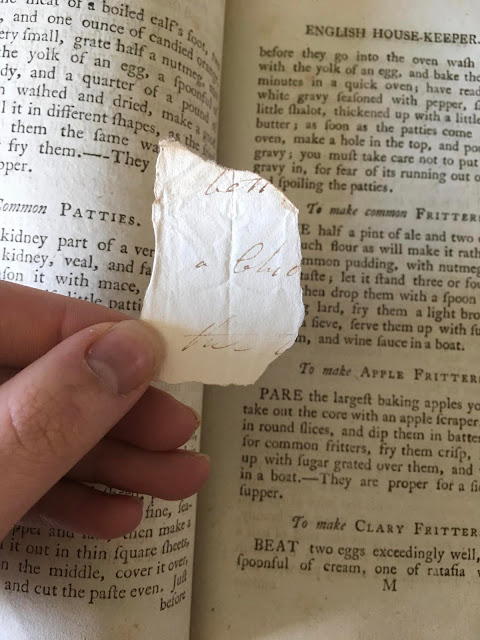

I hit a stumbling point, however, when it came to the main ingredient. The mince. Given that more and more people are (quite rightly) trying to eat less meat due to reasons that range from concern about the environment to moral issues, myself included, I knew that a good few of the people coming to my reading group would be vegetarian. All of the mince pie recipes I found in Victorian cookbooks and periodicals had, unsurprisingly, mince and beef suet in them, and so I was faced with a decision. I could either attempt to make the pies with a meat substitute, knowing that a lot of the original flavour of the pie would likely be lost, or I could alienate my friends and colleagues who aren't meat eaters. Before I abandoned the idea completely I had one last look at my collection of old cookbooks, and when I looked beyond the Victorian period and to the long nineteenth century I struck gold. A recipe in my copy of The Experienced English Housekeeper (1806) (which I picked up in a second-hand bookshop for just over £20): 'To make a Mince Pye without Meat.' Excellent. I could forgo the recipe with the tongue and look to the vegetarian alternative. This book from the very beginning of the nineteenth century had answered my prayers. It was nothing short of a Christmas miracle.

The cookbook itself is fascinating to me. Written by Elizabeth Raffald, and dedicated 'to the Hon. Lady Elizabeth Warburton, Whom the Author lately served as Housekeeper' it exemplifies a common trend in cookbooks of this era and before, that were written by ex-servants and dedicated to their Mistress or Master. Indeed, having a member of the gentry named on the title page would speak to the quality of the book's contents, as readers would know the recipes within were fitting for notable people. On the frontispiece it says 'Published as the 1st directs, by R. Baldwin, 31 July. 1782' which suggests the 1806 edition may be a reprint, but I am not completely sure. Other than what can be gleaned from the title page and the wonderfully detailed frontispiece of Mrs Raffald, however, I don't know much about the cookbook, but I will certainly look into it more detail. I was just blown away that the one 'vegetarian' mince pie recipe I could find was from such an early text.

The recipe itself took a bit of parsing. Despite the title it wasn't actually for a pie, but just the filling. It also seemed to make a huge amount of mincemeat, calling for three pounds of suet (which would have been beef suet historically, but I opted for a vegetable equivalent) and three pounds of apples, let alone the other fruits. I haven't quite worked out how different nineteenth century measurements are compared to ours today, but I do know that I didn't want to make that much mincemeat. So after some conversions and significant reductions to the amount of ingredients I ended up using the amounts that follow:

Sources:

(1833) 'Hereford", The New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal (London: Henry Colburn), p. 263

Dickens, Charles. [1843] 2009. A Christmas Carol (New York: Random House)

Greenwood, Victoria. 8 December 2017. 'The Strange and Twisted History of Mince Pies', online article, BBC, <http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20171208-the-strange-and-twisted-history-of-mince-pies> [accessed 10th Dec 2018]

Moore, Tara. 2009. Victorian Christmas in Print (New York: Palgrave Macmillan)

Raffald, Elizabeth. 1806. The Experienced English Housekeeper (London: R. Baldwin)

|

| The finished mincemeat. |

group I hosted we discussed Moore's book and how much the idea of the British Victorian Christmas is still embedded in our culture. Be it romanticised ideas of snowy walks through a foggy London, or John Lewis adverts that evoke ideas of charity and kindness through a Victorian lens, we seem very apt at forgetting that in reality Victorian life was difficult. Not every family had a benevolent employer who had been forced by ghosts to buy them dinner...

What I am interested in, of course, is how food plays in to all of this. After all, A Christmas Carol revolves around the concept of a traditional British Christmas dinner. The novel begins with Scrooge rejecting Fred's invitation to dinner and ends with him buying the Cratchits a glorious turkey, before he rejoins his family for celebrations over a laden table. So, if Dickens's novel began to define our ideas of what Christmas should look like, and a Christmas identity began to be really cultivated in the nineteenth century, it makes sense that the Victorians would have had a lasting influence on British Christmas cuisine.

|

| (The New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal) |

So I thought I would turn to one Christmas staple that is as popular now as it was in the nineteenth century: the humble mince pie. In origin, the mince pie is not Victorian and even precedes the long nineteenth century. This article explains in more detail that pies with mince in them, or mince pies, can be traced back to far earlier in British cuisine - http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20171208-the-strange-and-twisted-history-of-mince-pies - but I wanted to see what a nineteenth-century take on the mince pie was, thinking that I would bake some authentic festive treats for the aforementioned reading group.

I hit a stumbling point, however, when it came to the main ingredient. The mince. Given that more and more people are (quite rightly) trying to eat less meat due to reasons that range from concern about the environment to moral issues, myself included, I knew that a good few of the people coming to my reading group would be vegetarian. All of the mince pie recipes I found in Victorian cookbooks and periodicals had, unsurprisingly, mince and beef suet in them, and so I was faced with a decision. I could either attempt to make the pies with a meat substitute, knowing that a lot of the original flavour of the pie would likely be lost, or I could alienate my friends and colleagues who aren't meat eaters. Before I abandoned the idea completely I had one last look at my collection of old cookbooks, and when I looked beyond the Victorian period and to the long nineteenth century I struck gold. A recipe in my copy of The Experienced English Housekeeper (1806) (which I picked up in a second-hand bookshop for just over £20): 'To make a Mince Pye without Meat.' Excellent. I could forgo the recipe with the tongue and look to the vegetarian alternative. This book from the very beginning of the nineteenth century had answered my prayers. It was nothing short of a Christmas miracle.

The cookbook itself is fascinating to me. Written by Elizabeth Raffald, and dedicated 'to the Hon. Lady Elizabeth Warburton, Whom the Author lately served as Housekeeper' it exemplifies a common trend in cookbooks of this era and before, that were written by ex-servants and dedicated to their Mistress or Master. Indeed, having a member of the gentry named on the title page would speak to the quality of the book's contents, as readers would know the recipes within were fitting for notable people. On the frontispiece it says 'Published as the 1st directs, by R. Baldwin, 31 July. 1782' which suggests the 1806 edition may be a reprint, but I am not completely sure. Other than what can be gleaned from the title page and the wonderfully detailed frontispiece of Mrs Raffald, however, I don't know much about the cookbook, but I will certainly look into it more detail. I was just blown away that the one 'vegetarian' mince pie recipe I could find was from such an early text.

The recipe itself took a bit of parsing. Despite the title it wasn't actually for a pie, but just the filling. It also seemed to make a huge amount of mincemeat, calling for three pounds of suet (which would have been beef suet historically, but I opted for a vegetable equivalent) and three pounds of apples, let alone the other fruits. I haven't quite worked out how different nineteenth century measurements are compared to ours today, but I do know that I didn't want to make that much mincemeat. So after some conversions and significant reductions to the amount of ingredients I ended up using the amounts that follow:

|

| Mince pies, before baking |

- 200g of apples, peeled and sliced

- 175g of currants

- 150g of raisins

- 175g of mixed peel (the best alternative I could find to 'candied orange peel' and 'citron' the recipe asked for)

- 200g sugar

- 175g of vegetable suet

- 1tsp (around 3 to 4) crushed cloves

- 1 1/2 tsp grated nutmeg

- 2tsp ground cinnamon

- 200ml of brandy

Once I had converted the ingredients, I just mixed them together as per the recipe and let it all steep for a bit. It smelled amazing: boozey, spicy - the epitome of festive. The quantities I used made enough for 12 pies plus a spare jar to use later. I would have liked to let it marinade and mingle for a good while, but due to time constraints I only had a few hours before I had to make the pies.

This is where I have to make a confession. I did not attempt to make pastry from a nineteenth-century recipe, mainly because making pastry from a recipe from any time period is time consuming. So I bought a ready-made sheet of puff pastry and got on with it. Using a mug to cut out the bottoms, I employed my muffin tin to fit the pastry bases, filled them with mincemeat and then cut out little stars to top them off. After glazing with an egg wash, the pies were baked at 180 fan for 20 minutes - or until golden - and they were done.

They were delicious. Not at all unlike the mince pies we know and love today in their fruity spiciness. Infinitely better just by virtue of being homemade, I think. So, if you feel like being historical this Christmas, or bringing a bit of (vaguely) Dickensian cheer to your Christmas table, I would recommend knocking these up, or gifting a jar of mincemeat to someone to accompany a gifted copy of A Christmas Carol.

Lindsay

This is where I have to make a confession. I did not attempt to make pastry from a nineteenth-century recipe, mainly because making pastry from a recipe from any time period is time consuming. So I bought a ready-made sheet of puff pastry and got on with it. Using a mug to cut out the bottoms, I employed my muffin tin to fit the pastry bases, filled them with mincemeat and then cut out little stars to top them off. After glazing with an egg wash, the pies were baked at 180 fan for 20 minutes - or until golden - and they were done.

They were delicious. Not at all unlike the mince pies we know and love today in their fruity spiciness. Infinitely better just by virtue of being homemade, I think. So, if you feel like being historical this Christmas, or bringing a bit of (vaguely) Dickensian cheer to your Christmas table, I would recommend knocking these up, or gifting a jar of mincemeat to someone to accompany a gifted copy of A Christmas Carol.

Lindsay

|

| The finished article! |

(1833) 'Hereford", The New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal (London: Henry Colburn), p. 263

Dickens, Charles. [1843] 2009. A Christmas Carol (New York: Random House)

Greenwood, Victoria. 8 December 2017. 'The Strange and Twisted History of Mince Pies', online article, BBC, <http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20171208-the-strange-and-twisted-history-of-mince-pies> [accessed 10th Dec 2018]

Moore, Tara. 2009. Victorian Christmas in Print (New York: Palgrave Macmillan)

Raffald, Elizabeth. 1806. The Experienced English Housekeeper (London: R. Baldwin)

Comments

Post a Comment