Cookbook Tour #1: The Experienced English Housekeeper (1806)

Last week, I submitted material for the Annual Project Review which constitutes the assessment part of each year of my PhD. This hurdle (partially) overcome, I can now begin the next phase of my research: the fun part. It’s time to turn to recipes themselves. Given my intertwining focus on nineteenth-century recipes and on material technology, I am tracing recipes through time, focusing in particular on those instances in which recipe changes correspond with innovations in food and print technology. To that end, I am embarking on a number of case studies as my inroad into food in the nineteenth century. Beginning is always the hardest part, however.

So to start with - for the appetiser, if you will - I thought I would begin at home and turn to the small number of historical cookbooks that I own. I have five in total that I’ve stumbled upon in second hand bookshops or been given by kind friends (a shout-out here to Georgina Gale: the supplier to my Victorian cookbook habit) that range in date from 1806 to 1900-ish. I will admit that, so far, I have only cooked one recipe from one of these books: the meatless mince pie recipe from the 1806 book which I posted here around Christmas. What interests me as a budding book historian and lover of Victorian domestic culture, however, is the characteristics of these books as material objects.

As my last post touched upon, the cookbook as a physical object reveals much about how it has been used and by whom, through the smudges of flour on a favourite recipe or the scribbled notes in the margin. A cookbook actively embodies its purpose when it crosses the boundary between body and text in this way, both facilitating the consumption of food and bearing that food on its pages. This tangible reception history is surely only magnified when that cookbook has been around for nearly two centuries, then. So for this next sequence of blogs, which will be posted when I have the time and inclination, I will be taking you on a chronological tour of my nineteenth-century cookbook collection. I will endeavour to keep these posts short and sweet, but apologies if I get caught up in the discovery of a hidden jam recipe…

While my expertise does not yet extend to being able to date book spines or glean insights from the paper used, the aim of these posts is to whet my appetite for further research and highlight the interesting things that can be discovered through a look at these cookbooks as material objects.

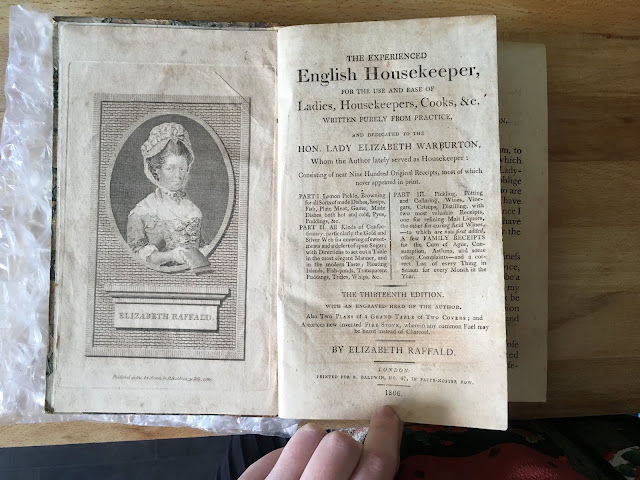

Cookbook Tour #1: The Experienced English Housekeeper, by Elizabeth Raffald

I happened upon this book before I had begun my PhD, at one of my favourite second-hand bookshops: Logie Steading Bookshop. Visiting on the first day of a holiday, I found the book and noted the 1806 label with interest. After flicking through I put it back on the shelf, however, as the cost (a pretty reasonable £25) put me off. A few days later I was back on the pretence of a walk - although I think my subconscious curiosity about the cookbook may have influenced that decision - and the next thing I knew, The Experienced English Housekeeper was being cautiously wrapped in bubble wrap for me with a couple of quid knocked off in deference to the detached cover. Bargain.

Elizabeth Raffald

Upon buying the cookbook I had never heard of the author, Elizabeth Raffald, or the book itself. Having done some research, however, I’ve found that Raffald is a prominent enough figure to have her own Wikipedia page. Indeed, it seems that Raffald was an entrepreneur long before it was the norm for women to have prominent business undertakings. So much so, that in 2015 she was shortlisted as one of six women who the public would vote on to be commemorated by Manchester’s first female statue in 100 years, though she lost out to Emmeline Pankhurst. What did Raffald do to leave such a legacy, then?

The first hint can be found on the title page of my copy of her cookbook, in the note that proclaims it ‘The Thirteenth Edition’. In the preface to the first edition, which is included in the book, Raffald notes that she ‘cannot but be apprehensive’ that her book will be met with the ‘contempt’ that cookbooks of that period often were (Raffald 1806: i). Raffald’s initial worries were obviously unfounded, however, as her book was so successful that it went on to have thirteen official editions and apparently 23 pirated editions. In 1773 she sold the book’s copywrite for a very pretty £1,400 – which in today’s money would have been around £175,000. Raffald wasn’t just an incredibly successful, wealthy cookbook writer, however. Gleaning information from some internet sources (not Wiki – the ultimate academic sin) I’ve discovered that she apparently opened the first registry office in Manchester which allowed servants to get married, and ran two coffee shops, an indoor and outdoor catering business and a school which taught domestic servants and supplied wealthy families with staff. Long before the time when female cookbook writers became brands in themselves (it’s a little-known fact that Isabella Beeton died when she was 29, as publishers kept on using her name to sell cookbooks), Elizabeth Raffald was creating a successful name and business for herself, founded upon her domestic experience.

The Cookbook

This sense of success and authority is tangible throughout the pages of the cookbook itself. A frontispiece shows a portrait of Raffald, and the fine clothing and assured facial expression that she wears pair with the fact that she is holding a book (often used as a prop in portraits to indicate the subject was a person of letters) to convey that she was someone whose advice could be trusted. Indeed, this notion of reliable authority is a theme that runs through the text. Opposite Raffald’s portrait is a subtitle, which declares that the book is ‘dedicated to the Hon. Lady Elizabeth Warburton, Whom the Author lately served as Housekeeper’ (Raffald 1806: title page). During this time, and indeed into the nineteenth-century, it was common for the female authors of domestic advice guides or cookbooks to credit their experience to their time serving as a housekeeper. If, like Raffald, you had served a Lady in an important, titled family, then your recipes and advice would be viewed as reliable. Just like a book review from a reputable newspaper or a famous author on the cover of a bestseller makes us buy books today, this name-dropping was an act of advertisement.

Indeed, in addition to the preface there is a dedication to Lady Warburton in which Raffald humbly begs Warburton to allow Raffald to share her domestic knowledge with ‘a great number of my friends’ (Raffald 1806: dedication). In this dedication, Raffald says her book was written to aid people in improving themselves, noting she has written the recipes in plain language so they may be understood by people of ‘the meanest capacity’ (Raffald 1806: dedication). Here, Raffald was ahead of the curve. Way before the influx of books in the mid-nineteenth century that were targeted at the expanding and upwardly mobile middle-classes, Raffald is hinting that her book may facilitate social climbing: an idea that would have been slightly controversial in the late-eighteenth/early-nineteenth century. Given that she opened a registry office that allowed servants to marry, however, we can assume that Raffald was something of a humanitarian, and her cookbook consolidates this.

In terms of the book’s contents, there are several interesting things to note. The cookbook doesn’t have a contents page beyond the paragraphs on the title page that summarise the chapters’ contents. These lack page numbers, and I was unsurprised that Raffald’s cookbook might be a little hard to navigate. Having read a world of criticism on Victorian cookbooks that lauds Isabella Beeton for her ordering skills and indexing in The Book of Household Management (1861) I was, however, surprised that this much earlier cookbook does have an index. I assumed that the organisation of cookbooks in this manner was a later, Beeton-esque innovation. On the contrary, Raffald’s index is alphabetical, organised via helpful headings and subheadings, and clearly indicates the page numbers on which recipes can be found - making the whole text easy and efficient to use.

There are no advertisements per se in this cookbook, but there is a fascinating plate which depicts ‘A curious new invented FIRE STOVE, wherein any common Fuel may be burnt instead of Charcoal’ (Raffald 1806: title page). While the plate doesn’t indicate where readers may buy such a stove, its inclusion is an advertisement in itself and I was shocked to find such a detailed representation of a new cooking technology in such an early cookbook. I will definitely be pursuing this stove further in my archival research…

There are no advertisements per se in this cookbook, but there is a fascinating plate which depicts ‘A curious new invented FIRE STOVE, wherein any common Fuel may be burnt instead of Charcoal’ (Raffald 1806: title page). While the plate doesn’t indicate where readers may buy such a stove, its inclusion is an advertisement in itself and I was shocked to find such a detailed representation of a new cooking technology in such an early cookbook. I will definitely be pursuing this stove further in my archival research…

In addition to this plate there is a beautiful meal plan, illustrating how readers should arrange the dishes on their table for the first course of the meal. This extravagant, inconvenient trend for serving dishes at the same time was the service á la française that dominated British dining rooms until it was replaced by dinner á la russe in the mid-nineteenth century. At this point, new cooking technologies meant that middle-class families could afford to keep food warm in the kitchen and serve it on a course-by-course basis, instead of all at once.

Raffald’s recipes themselves are typical of those I have seen from this period. They are formed of one or more paragraphs and lack ingredients lists or timings, meaning that readers would have to read the whole thing before they began cooking to ascertain what they needed, and how it was prepared. There is a predictable emphasis on meat, soup and gelatine in the cookbook, though I was surprised by some of the exotic ingredients it mentions, including cayenne pepper and parmesan cheese. Another striking trend shown through these recipes is the preoccupation with appearance. Raffald’s recipe for mock turtle is painstakingly labour intensive, and other recipes include ‘To boil Brocoli in Imitation of Asparagus’, ‘A pickle in Imitation of Indian Bamboe’, and one for something called ‘A Fish Pond’ - which seems to be a clear jelly in which fish are suspended as immortalised if in water. Delicious. These recipes are all clearly invested in the appearance of food - what you served on your table was a clear social marker to the people you entertained. But to return to her democratic plain language, Raffald is once more giving her readers the secret to creating the impression of taste and wealth. If you don’t have asparagus, she will show you how to make your broccoli look like asparagus, and maybe no one will notice. In fact, you'd hope they were so dazzled by your fish pond that they wouldn't care...

Raffald’s recipes themselves are typical of those I have seen from this period. They are formed of one or more paragraphs and lack ingredients lists or timings, meaning that readers would have to read the whole thing before they began cooking to ascertain what they needed, and how it was prepared. There is a predictable emphasis on meat, soup and gelatine in the cookbook, though I was surprised by some of the exotic ingredients it mentions, including cayenne pepper and parmesan cheese. Another striking trend shown through these recipes is the preoccupation with appearance. Raffald’s recipe for mock turtle is painstakingly labour intensive, and other recipes include ‘To boil Brocoli in Imitation of Asparagus’, ‘A pickle in Imitation of Indian Bamboe’, and one for something called ‘A Fish Pond’ - which seems to be a clear jelly in which fish are suspended as immortalised if in water. Delicious. These recipes are all clearly invested in the appearance of food - what you served on your table was a clear social marker to the people you entertained. But to return to her democratic plain language, Raffald is once more giving her readers the secret to creating the impression of taste and wealth. If you don’t have asparagus, she will show you how to make your broccoli look like asparagus, and maybe no one will notice. In fact, you'd hope they were so dazzled by your fish pond that they wouldn't care...

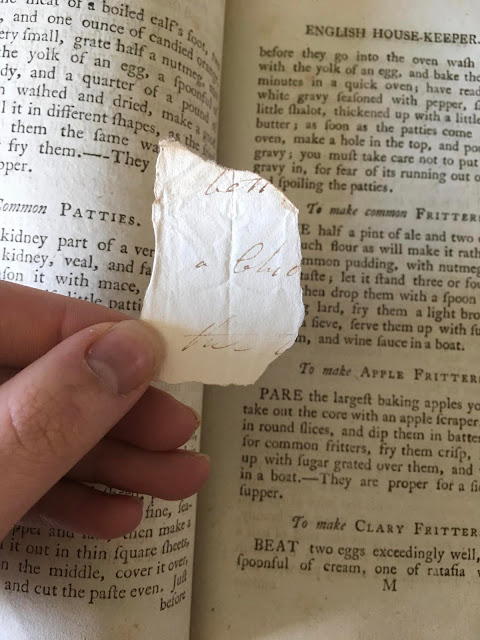

Aside from the written contents of the book, there are some treasures to be found in the marginalia. A signature written in elegant, cursive script tells me that at one point this book belonged to a Mrs L Swan, from Beccles. Within the cookbook I found a tantalising scrap of paper, also written in a faded, cursive hand. The scrap is too small to be legible, but it leads to an endless number of questions. Was it written by Mrs L Swan? Who was Mrs Swan, and when did she own this book during its 200+ year history? Did the scrap contain a recipe, changed by the cookbook’s reader? Or was it something totally different, a love letter, a gift note, and where does the rest of it now reside?

While I could go on and investigate The Experienced English Housekeeper’s recipes, pages and materiality in more detail (even the masking tape that now holds the cover to the pages is itself a fascinating piece of the book’s history), this blog post has already been meandering enough. The cookbook’s existence as an object that transcends time, classes, readers and even the recipes contained within its pages, makes it a fascinating object for cultural study. And all this before we even get around to cooking the recipes Raffald wrote and embodying her history and the history of all her readers in that way. One thing remains prominent as I embark on these individual case-studies and my wider research, however. As I sit with this book on my lap, I am just one of many people that have owned or read this particular cookbook. Considering all those before me who perused, cooked from, cherished or simply picked up this book before putting it back on a bookshop shelf, highlights a poignant notion that if household objects are properly used, loved, looked after and passed on, then we become part of their lives rather than the other way around.

While I could go on and investigate The Experienced English Housekeeper’s recipes, pages and materiality in more detail (even the masking tape that now holds the cover to the pages is itself a fascinating piece of the book’s history), this blog post has already been meandering enough. The cookbook’s existence as an object that transcends time, classes, readers and even the recipes contained within its pages, makes it a fascinating object for cultural study. And all this before we even get around to cooking the recipes Raffald wrote and embodying her history and the history of all her readers in that way. One thing remains prominent as I embark on these individual case-studies and my wider research, however. As I sit with this book on my lap, I am just one of many people that have owned or read this particular cookbook. Considering all those before me who perused, cooked from, cherished or simply picked up this book before putting it back on a bookshop shelf, highlights a poignant notion that if household objects are properly used, loved, looked after and passed on, then we become part of their lives rather than the other way around.

Lindsay

Sources:

Raffald, Elizabeth. 1806. The Experienced English Housekeeper, 13th ed (London: R Baldwin)

6 April 2013. 'Georgian chef Elizabeth Raffald's recipes return to Arley Hall menu, BBC News <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-22048430> [accessed 27.4.19]

Williams, Jennifer. 20 October 2015. 'Shortlist of six iconic women revealed for Manchester's first female statue for 100 years', Manchester Evening News <https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/shortlist-six-iconic-women-revealed-10296652> [accessed 27.4.19]

Comments

Post a Comment