Beginnings: An Apple a Day

While it

has taken all my self-control not to open this post with some kind of joke

about apples and doctors and doctorate students, something along those lines

would be a fitting way to reintroduce my revamped, repurposed blog. For those

of you who read my musings about food and eating from a couple of years ago, I

hope you will still find something of interest here as I reopen ‘Well Fed and

Well Read’ in keeping with the new, exciting chapter of my life: my PhD.

Indeed, as those previous posts show, my fascination with food, eating and

literature is longstanding – something that has grown in the last year as I

undertook an MLitt in Victorian literature and applied for my PhD project: ‘The Technical Recipe: A Formal Analysis of

19th Century Food Writing.’ To correspond with this new degree, and

all I hope to achieve in the next few years, I am relaunching my blog as a

means of communicating my research, getting my thoughts out of my head and into

the ether (what is a blog after all, other than void screaming?), and hopefully

providing those of you interested in food, literature and history with some

entertaining reading!

So, first

of all, some introductions (I would like to note that not all posts will be

this long, as my first consists of an introduction to my research as well as a Victorian

recipe). My PhD project, which I am undertaking over the next three years

between the University of Glasgow and the University of Aberdeen thanks to

funding from the SGSAH, will be – I hope – the perfect marriage of my research

interests in Victorian literature and my passion for food and cooking. Lying

between the disciplines of English Literature and the History of Science and

Technology, I plan on investigating nineteenth-century food recipes as what I

believe recipes are: a valuable and underappreciated form of literature,

culture and historical insight. Having only started in October, my project is

still very much in formation as I investigate the current critical field and

try and decide how to structure my investigation in the most imaginative and

effective way.

One thing

I do know, however, is this: recipes are interesting, fascinating, fun and

collaborative forms of writing from which all sorts can be gleaned about the

reader, the writer, the culture they lived in, the technology they were using,

and the social significance food carries at different points throughout

history. Most importantly, a recipe is a form in which all this can be

understood not only through analysing the words on the page and the culture they

invoke, but also by using a recipe as the writer intended – by cooking!

After all,

a recipe is not a static form, and that is perhaps its most interesting quality.

Recipes are written to instruct a reader how to make something that will change

the world around them. It may allow them to produce food to consume, serve to a

loved one or an employer, sell, impress important people, ascend social circles

or even poison someone. Recipes open the door to nostalgia, allowing us to

recapture our memories through the process of cooking and eating something that

brings us back to the past, be this in a positive or negative way. They are

passed down between generations, handwritten in notebooks, read in magazines

and instantly thrown away, succeeded or failed at, and I believe are one of the

only forms of writing with the potential to carry such cultural importance.

The potential facing a reader when they select and use a recipe is vast and my research

is intrinsically interested in all the possibilities that extend, like curls of

steam from a bubbling pan, outwards from interacting with and enacting recipes.

As such, I

will use this blog to reach out to other readers and cooks via the recipes I

study and reproduce as part of my research. I would love to hear from anyone

interested in my work, should you have a favourite recipe to share or a nineteenth-century

resource you think I should peruse. I believe collaboration is intrinsic in both

cooking and research - hence my writing this blog once more. I aim to post fairly regularly, sometimes including interesting recipes I find, sometimes musings on other forms of food writing and sometimes, I'm sure, just some rambling thoughts.

Now, the

rest of this blog is dedicated to my first attempt at cooking a

nineteenth-century recipe, and who better to start with than the iconic,

canonical Mrs Beeton?

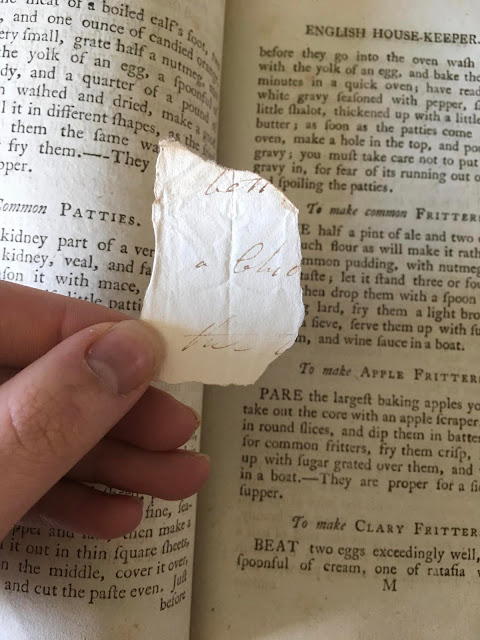

In the

name of full disclosure I should say I am actually cooking two recipes here. First

of all, I turned to The Englishwoman’s

Domestic Magazine, which was published between 1852 and 1879 predominantly

by Samuel Orchart Beeton (editor), who married Isabella Beeton in 1856. Shortly

after this, she took over the cooking column in the magazine. Her increasing

control over this column provided her with an extensive resource of material

for her canonical text Mrs Beeton’s Book

of Household Management, which was published in 1861 and contained a vast

array of recipes and household advice, from various (often uncredited) sources.

If anyone is interested in Isabella’s life in more detail, I would highly

recommend Kathryn Hughes’s 2005 biography The

Short Life and Long Times of Mrs Beeton, which gives far more detail about

her than I could ever hope to include in a blog post!

But I

digress – as I say I turned to the EDM for

a simple recipe to try my hand at, and since I was visiting home at the time

and my Dad’s garden was yielding a glut of apples, I used the British

Newspapers 1600-1900 Gale Primary Resources database (accessed via the GU library website)

to search for an ‘apple recipe.’ Several came up - including many for jelly,

tarts and some interesting-sounding stuffings – but I opted for something

simple: Stewed Apples with Custard, delightfully captioned 'a pretty dish for a juvenile supper' (Beeton 1861b: 48). Now, this is where the Beetons’s

master-minded advertising came into play, as lo and behold the custard portion

of the recipe was not included in the periodical at all but instead readers

were instructed to ‘have ready quite ½ pint of custard made by recipe No. 1423,

in Mrs. Beeton’s “Book of Household Management”' (Beeton 1861b: 48). Ingenious! Now the Victorian

reader has to go and buy the Beetons’ book if they want their apples, which

tells you something of the way that print culture worked at the time of the

Beetons’ heyday. Already, this short recipe tells the reader something about print technology, culture and the way that even simple recipes in periodicals were intrinsically involved in the hard sell.

Luckily

for me, an 1861 copy of Beeton’s famous cookbook is available - free of charge - on the Wellcome Library website, and so I set off picking apples

and cooking. While the recipe in the EDM is not credited to an author, in all likelihood Isabella Beeton would have been responsible for sourcing or writing it at this time. Ironically, by 1861 it would likely have been unusual for Beeton’s

reader to be able to go and pick their own apples as the majority of Victorians

lived in increasingly urban settings mid-century, and so my quaint fruit

collection might even have been a nostalgic wish for a reader back them.

|

| Stewing apples. |

|

| Milk, sugar and lemon steeping by the fire. |

The recipes themselves (pictured above) were easy to follow, and I think this would be true regardless of your cooking talents. The apples were simply peeled, cored and then boiled in a syrup-like water. The custard was more technical, and involved steeping milk by the fire (I again managed to do this at home, but in my flat it would have been a half-hearted turn to the radiator) as well as a LOT of stirring. Thankfully my Mum was on hand to help out when my arm began to ache, though at one point I turned around to find her using a temperature probe to make sure the milk didn’t boil – not very Victorian indeed. Her suggestion that we try microwaving it was swiftly rejected.

By the end

of a process that was pretty lengthy for a simple dessert, the result was

admittedly delicious. I tried to follow the recipes as closely as possible, presenting the apples 'in a glass dish' (Beeton 1861b: 48) and indeed steeping the milk by the fire, but I will admit we ate the apples warm rather than cold.

|

| The finished article! |

The custard was rich and lemony, and the apples sweet, but spiced delicately with cloves so the dish was not overpowering. Both recipes are attached and referenced, in case any readers fancy trying out some Victorian apples for themselves, but my overall advice would be this – Beeton’s apples are delicious, and if you have the time the lemony custard is definitely worth the arm ache. Bird’s Custard powder, however, was created by Alfred Bird in 1837 – so if you were to grate some lemon zest into it you would not be being anti-Victorian whatsoever, and you might finish the dish in time to watch Bake Off.

Lindsay

Sources:

Beeton, Isabella. 1861a. Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management (London: S.O. Beeton) <https://wellcomelibrary.org/item/b21527799#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=6&z=-0.3981%2C0.3758%2C1.6748%2C0.9>

Beeton, Isabella. 1 February 1861b. 'Recipes: Stewed Apples and Custard', Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine, p. 48

Hughes, Kathryn. 2005. The Short Life and Long Times of Mrs Beeton (London: Fourth Estate)

Comments

Post a Comment