On the weekend of my twenty-fifth birthday, I roasted my first ever chicken. It was October 2020 and Glasgow was in an ongoing lockdown. As someone who likes life to be a pattern of overlapping routines and rituals, I couldn’t overindulge in my typical birthday habits: at least a week filled with friends, family, spontaneous purchases and even more food and wine than usual. I normally spend the day baking my own cake, which I then share over the next week with colleagues and friends to draw the festivities out further. In the absence of these beloved habits (though I still made a cake – chocolate olive oil), it felt like the perfect time to begin a new one. I had been rereading Nigella Lawson’s How to Eat, and the first recipe in it is for ‘Basic Roast Chicken’. She opens with a question: ‘You could probably get through life without knowing how to roast a chicken, but the question is, would you want to?’ (2018: 6). As I hit a quarter of a century – a birthday that doesn’t really signify anything, but still seems significant somehow – I realised that no, I did not want to live without knowing how to roast a chicken. Given that I like to think I know how to cook and eat well, I was ashamed to have stumbled within the first 6 pages. My mind was made up. Roasting a chicken, an act inextricable from love, tradition, and care, was the perfect choice for the new ritual that would open my next twenty-five years.

Before this I had eaten many, many roast chickens, and loved them all. At Christmas my family often has chicken instead of its dryer, blander cousin. In autumn it comes with honeyed carrots and parsnips, and in spring with lettuce, freshly podded peas and tender, pale-green broad beans. I even loved the roast (or perhaps poached? It was always pale and unusually soft) chicken that occasionally appeared underneath the lukewarm lights of the school-dinner counter, served with a thin beige sauce and gritty Aberdonian skirlie. The first meat I ever tasted was roast chicken – the cold, rotisserie type with puckered skin from Marks & Spencer that was a staple in the house of my Granny, who wasn’t much of a cook. I’ve been told how she looked on in triumph as I grabbed a drumstick with tiny greedy hands as my (then vegetarian) parents looked on in shock.

My Mum makes a wonderful roast chicken, with a simple tangy white wine gravy cooked in the roasting tin that I am always trying to emulate. There’s no recipe, of course. I’ve asked. It’s just done by feel. All the chickens my Mum has cooked throughout my life remind me of home. The smell of a roasting chicken wafted through the house I grew up in all through the year. If you were outside in the garden it was somehow more potent, made extra buttery by summer warmth or sharp and significant in the cold winter air. It smells like warm gold and wine and a goodness that is hard to put into words. As Nigella writes when recalling the roast chickens of her childhood, ‘it’s partly for that reason that a roast chicken, to me, smells of home, of family, of food that carries some important, extra culinary weight’ (2018: 7). That concept, of ‘extra culinary weight’, captures the significance of roast chicken perfectly. It is not just a meal, but a process layered with emotional meaning. Every time I smell a chicken roasting, I am smelling all the chickens I have eaten in the past.

But despite this formative love of the roast chickens which have fed my body, mind, and heart, I had never cooked one myself. Something about roasting an entire bird felt daunting, particularly as when I moved away from home I was cooking for myself and perhaps a partner, rather than my whole family. The idea of salmonella hiding somewhere I couldn’t check in the entirety of a whole animal was oddly frightening given that I’m a competent, comfortable cook. But on my twenty-fifth birthday I craved that wine-gold smell and its connotations of comfort and love almost more than I wanted to eat the chicken itself. I took myself off to the supermarket, bought the highest-quality bird I could find, and began.

For that first chicken I cooked Nigella’s recipe, with a healthy sprinkle of advice given over WhatsApp by my Mum. It would have felt rude not to, and Basic Roast Chicken was what I was aiming for. Half a lemon in the cavity, breast coated in a generous layer of butter, salt and pepper, and in the oven at 180° for around an hour and a half. As my flat began to fill with that promisingly familiar smell, I was full of anticipation. I still remember bringing it out when it was done. It was perfect. Gilded, it almost glowed with crispy, salty skin that my Mum eats as she lets her chickens rest and finishes the rest of the cooking: a ‘chef’s treat’. My years of hovering in the kitchen were always rewarded though, and she still lets me have some too. To this day I think that the skin, stripped straight off the piping-hot bird and eaten with a clandestine, conspiratorial air, is the best bit. But this time it really was

my chef’s treat, and in my excitement I generously and triumphantly gave some to my boyfriend, wanting him to bask in the golden glow of my success too.

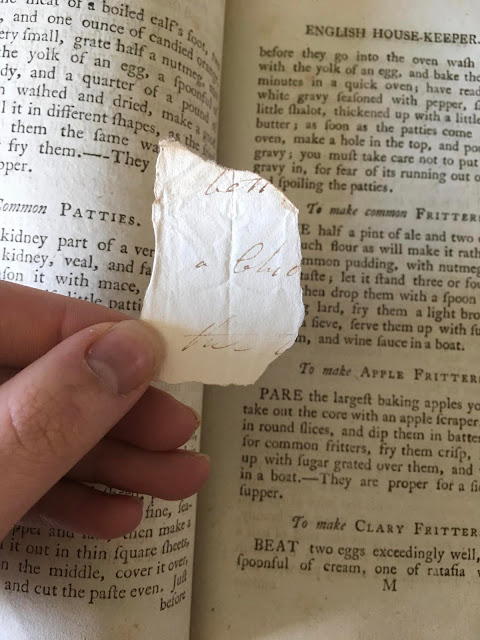

|

| My first roast chicken |

I’m twenty-six (and a half) now, and since my first I have roasted dozens of chickens. Not every weekend, but in the winter it certainly gets close. I feel I must make up for lost time. I’ve tried lots of different recipes – Ottolenghi’s preserved lemon spring chicken is a favourite. I’ve blitzed wild garlic into the butter I rub under the skin, or used a dry rub of cumin and smoked paprika. Sometimes I opt for pomegranate molasses to make the golden skin rich and sweet, and sometimes I half roast, half poach the chicken in a bed of orzo, stock, parmesan and vegetables (another Nigella recipe). I almost always tip the chicken’s juices into a pan and combine with a sharp white wine to make my Mum’s gravy, sometimes with a sprinkle of flour or added shallots, lemon juice or butter. I don’t tend to skim the fat, partly because I can’t be bothered and partly because I like that it turns any leftover gravy into a punchy jellified stock that improves any dish. Honestly, I’d spread it on bread. Without fail, the way the wine emulsifies with the fat and juices to form a creamy, opaque gravy always seems like some kind of alchemy. It’s a dependable process but is different enough each time based on the size of bird or the fattiness of the meat that it’s exciting – it feels like magic when it works out.

I think that’s what I adore about roasting chickens. It’s a process that very quickly becomes familiar – I no longer need a recipe and rarely use my meat thermometer, trusting my judgement instead. But it still has an undeniable air of magic about it. The pale, pasty body gets transformed into a gleaming, golden centrepiece in a flourish that is reminiscent of Cinderella’s fairy godmother turning the pumpkin into a glimmering carriage with a wave of her wand. The burnished smell which accompanies the cooking adds to the sense of wonder, and no matter what kind of day I’ve had roasting a chicken is guaranteed to soothe and warm me.

Once the chicken is roasted, I relish its afterlife. When the dinner is eaten and dishes are washed, I tend to put on music and pour another glass of wine before attending to the carcass. I meticulously separate the leftover meat from the bones, taking my time over each one and relishing the oddly visceral way the fat coats your skin. Then at some point in the next couple of days I make stock, which once more fills the flat with a delicious savoury steam – slightly different from the smell of the chicken roasting, but just as nourishing. In a world when the gap between the food we eat and where it is produced is often disconcertingly large, I love being able to fully pay my respect to the animal I’m eating by making sure I get every last scrap of goodness from it. The stock and leftover meat go in the freezer, marked as the base for a soup or risotto, and the act of roasting a chicken on a Sunday is extended so it feeds me for several more days or weeks until my reserves are depleted, and then I begin again.

These repeated motions – preparing, cooking, basting, carving, eating, pulling-apart of flesh, boiling of bones, freezing, reheating and eating once more – soothe me in a way that little else does. I’ve written before about how I cook risotto when I have writer’s block, as the rhythmic stirring loosens the knot in my brain and gets the words flowing again. Roasting a chicken has a similar effect. Because it takes a couple of hours all in, it forces you to slow down and set your mental clock to a different culinary time zone. I love preparing the sides for a roast dinner between bastings, but that’s almost another piece of writing in itself. It’s the perfect Sunday activity, but sometimes I seek the same furtive, decadent pleasure I get from having a bath in the middle of the day and roast a chicken during the week. It’s such a versatile food that it suits any season or notion, and even though buying a good-quality chicken is an expensive luxury I get so much from it in terms of future meals and emotional satisfaction that it still feels (almost) economic.

More than its deliciousness, it is this process of roasting a chicken which I have come to unabashedly love. It grounds me in memories, emotions, and traditions which somehow feel larger than my own. I know friends and family who love roasting a chicken as much as I do, and though we don’t speak about it I feel certain it carries a similar kind of significance for them. That wine-gold smell surrounds people in comfort and warmth, and for me, roasting a chicken is a unifying expression of love. Now that I’ve started, there’s no going back. Because really, why would you want to go through life without knowing how to roast a chicken?

Lindsay

Comments

Post a Comment