An Ode to the Cookbook: Past, Present and Future

To begin this post, I can do no better than to thank Twitter. Well, not Twitter per se (I lose too many hours procrastinating on it to be fully indebted) but the many lovely people I engage with there, who share my interests in food and food history. For if it weren’t for two Twitter-pals tagging me in a call for papers, I may never have come across the symposium at the University of Portsmouth: ‘Cookbooks: Past, Present and Future’ - http://creativespace.cci.port.ac.uk/event/cookbooks-past-present-and-future/.

As most people who know me know, my PhD project means I am lucky enough to spend my time perusing recipes, cookbooks and food writing. For research purposes, I focus on texts from across the nineteenth century, considering everything from early manuscript recipe collections to recipes in the domestic columns of periodicals, and cookbooks from Beeton’s canonical Book of Household Management (1861) to the lesser-known How I Managed My House on Two Hundred Pound a Year, by Eliza Warren Francis (1864).

My interest in cookbooks and recipes, however, was not born with the start of my PhD. In my parent’s home, we are lucky enough to have at least three bookshelves and numerous stacks dedicated solely to cookbooks. Well I say lucky, but my Dad has bemoaned their presence more than a few times due to dust and stubbed toes…

I have those books, the ideas they sparked and my Mum’s deft and imaginative adaptation and creation of recipes to thank for my talent in the kitchen, and the shape of my academic career thus far.

In my flat I am also lucky to own a bookshelf that is home to nothing but cookbooks. At last count I have 68, including a small number of nineteenth-century texts – and collecting them is a habit that shows no signs of slowing. When I have the cash and inclination to treat myself to a new book, 9 times out of 10 I opt for a cookbook over a novel these days.

In my flat I am also lucky to own a bookshelf that is home to nothing but cookbooks. At last count I have 68, including a small number of nineteenth-century texts – and collecting them is a habit that shows no signs of slowing. When I have the cash and inclination to treat myself to a new book, 9 times out of 10 I opt for a cookbook over a novel these days.

I justify it to myself because they’re beautiful, enjoyable to read and useful. Pouring over the glossy pictures and mouth-watering descriptions of food and cooking processes is almost as much of a joy as eating. Again, this is not an argument that always sways my wannabe-minimalist boyfriend.

Sorry (not sorry), but my cookbooks will never be Kondoed.

So when the cfp for the ‘Cookbooks: Past, Present and Future’ symposium was brought to my attention, it was as if someone had trawled the inside of my mind – or indeed, my twitter feed – and designed the perfect academic conference. A day of intellectual debate about all aspects of the cookbook: their past, use of gender and other ideologies, design, and future in an increasingly digital world, etc. I couldn’t imagine anything more delicious. I sent off an abstract which was accepted and was fortunate to secure funding from the University of Glasgow to cover the cost of attendance, travel and accommodation. I was off.

I won’t spend too much of this post going over the details of my paper but I will briefly summarise it here. Titled ‘Characters in Cookbooks: The Victorian Trend of the Fictional Housewife,’ my discussion centred on two Victorian cookbook authors: Alexis Soyer (1810-1858) and Eliza Warren Francis (1810-1890). Taking a cookbook from each, Soyer’s Modern Housewife, or Ménagère (1849) and Warren Francis’s How I Managed my House on two hundred pounds a Year (1864), I investigated the way these cookbooks differed from typical Victorian cookbooks. Rather than practical collections of impersonal, ordered recipes, both of these books were unusually written from the perspective of fictional housewives. Milly Allison’s memoir in My House, and the epistolary exchange between Hortense and Eloise in Modern Housewife, frame recipes with intimate information about the narrators and personable characterisation that is friendly and entertaining. Both authors use relationships between women to present Victorian cooking as a dialogic exchange that is dependent on and bolstered by female relationships, and the use of characterisation invites the reader into the text as a friend. As part of the panel ‘Gender, Identity and the Cookbook,’ I investigated the way that the authors’ gender influenced how they wrote their fictional housewives, demonstrating that gender and characterisation were publishing strategies in these Victorian cookbooks.

I won’t spend too much of this post going over the details of my paper but I will briefly summarise it here. Titled ‘Characters in Cookbooks: The Victorian Trend of the Fictional Housewife,’ my discussion centred on two Victorian cookbook authors: Alexis Soyer (1810-1858) and Eliza Warren Francis (1810-1890). Taking a cookbook from each, Soyer’s Modern Housewife, or Ménagère (1849) and Warren Francis’s How I Managed my House on two hundred pounds a Year (1864), I investigated the way these cookbooks differed from typical Victorian cookbooks. Rather than practical collections of impersonal, ordered recipes, both of these books were unusually written from the perspective of fictional housewives. Milly Allison’s memoir in My House, and the epistolary exchange between Hortense and Eloise in Modern Housewife, frame recipes with intimate information about the narrators and personable characterisation that is friendly and entertaining. Both authors use relationships between women to present Victorian cooking as a dialogic exchange that is dependent on and bolstered by female relationships, and the use of characterisation invites the reader into the text as a friend. As part of the panel ‘Gender, Identity and the Cookbook,’ I investigated the way that the authors’ gender influenced how they wrote their fictional housewives, demonstrating that gender and characterisation were publishing strategies in these Victorian cookbooks.

While I could go on and on about my topic (if you want to hear the full 15-minute talk, just stop me in the street) the purpose of this post is to give credit to the wider symposium and what it embodied. Organised by Dr Laurel Forster from the University of Portsmouth, the event was attended by people from all over the world. Speakers came from the UK and as far as the USA and Israel. We spoke about everything from the Clean Eating fad and orthorexia nervosa to the graphic design of Israeli cookbooks, the technological kitchens of the future, and Fanny Cradock. One brilliant paper from Malcolm Thick compared an eighteenth-century printed cookbook to the manuscript it was based on, which he owned and showed to us all. The day ended with a talk from the lovely bestselling author Jack Monroe, and a panel with her, Lulu Grimes (BBC Good Food editor) and food vlogger Katie Quinn. It was a day of variety, as people from different backgrounds, disciplines and communities came together to discuss what cookbooks meant to them. A selection of different ingredients that combined to create a delicious meal, perfect for sharing - if you will.

What the symposium, the people I met there, and the papers I listened to have highlighted is that cookbooks are makers and markers of community and culture.

It can be easy to get lost in my nineteenth-century world of Bovril and suet puddings, but cookbooks and recipes throughout history and from the world over have always encompassed and recorded human relationships, and I believe they will continue to.

All in all, I am thankful to Laurel Forster for organising and convening such a wonderful event. Bringing people from across the world to have these discussion opens many exiting doors for future discussions, thoughts and projects. Moreover, I now have another excuse to expand my cookbook collection. Victorian or otherwise, they all count as research, right?

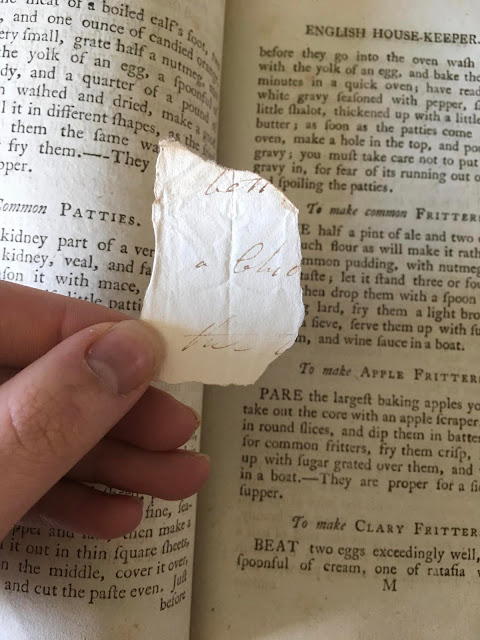

Whether the issues captured in cookbook pages are political and ideological - like the colonisation of India, embodied in the sandwiching of a mulligatawny soup recipe between different English broths in Victorian cookbooks – or utterly personal and small-scale, like the handing down of handwritten scraps, cuttings and recipes in the ring-bound

Whether the issues captured in cookbook pages are political and ideological - like the colonisation of India, embodied in the sandwiching of a mulligatawny soup recipe between different English broths in Victorian cookbooks – or utterly personal and small-scale, like the handing down of handwritten scraps, cuttings and recipes in the ring-bound

If food is what sustains us, then cookbooks are the texts that record our life’s blood.

Lindsay

Comments

Post a Comment